[transitionslider id=”1″]

[su_spacer]

Lobster season was into its first few days when Josh and his friend, Keith Wyer, could not wait to dive for those tasty bugs. They took off from a La Jolla beach at night, and it wasn’t long before Josh found a big ledge and dove down. His dive light spotted many sizable/legal antennae wedged deep inside. He was about to snag a couple when he suddenly felt a hard thump on his head and shoulder.

Thinking it was Keith and being a bit perturbed since he didn’t want to cause a disturbance that would send the crustaceans back into the deep, his head turned a bit, and, from the corner of his mast, he saw the deep eyes, broad head and blunt snout of a broadnose sevengill shark showing off those razor-sharp teeth.

In instant reaction, he whacked the nose of the predator with the dive light. The shark’s head jerked back in surprise and spun around to come back at him with a beady stare at his would-be prey – then had second thoughts and took a few fast tail waves in retreat while Josh’s dive light kept a watchful beam as it disappeared into the blue darkness.

Welcome to Josh Liberty’s world.

“It’s not seeing a shark that worries you, it’s when you can’t see them that worries you” … Josh Liberty

FREE DIVING IN LA JOLLA, CALIFORNIA

If there was ever a coastal town that excelled in diving and the dive clubs that were associated with diving culture, La Jolla, California, was it. No doubt the most famous of these organizations was the world-renowned Bottom Scratcher.

Josh Liberty was a product of La Jolla’s dive culture.

When you first meet him, the first thing you admire is his humble demure. Now add an average build and size, and you would never think he’s even capable of jumping into the matrix of deep blue water, diving down 40 to 70 feet, holding his breath for minutes, transforming into an aggressive, calculated hunter of big-game fish. It’s a skill not everyone can be taught, and one that requires a natural ability.

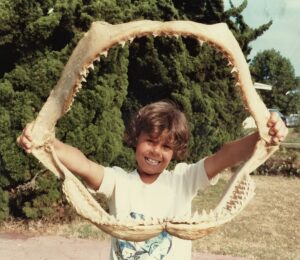

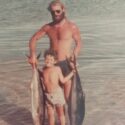

Josh was very blessed. He was born to Keith and Mary Jane Liberty in September 1970. His dad, Keith Liberty (of Ocean Fresh fame), was another La Jolla waterman legend. Since the day he was old enough to hold a rod and reel, his dad taught him how to fish (some say, Keith put a fishing pole in his hand before a pacifier). When Josh was around ten years old, Keith took him just south of Rosarito, Mexico. He had bought him a mask and snorkel and taught him “the basics” in a tide pool.

But Josh still wasn’t impressed. The water was murky, and even if he was in waist-deep waters, submerging his head into a wet environment made him feel a bit uneasy — land fishing or fishing off a boat offered more security.

A few years later, his dad got him a small single-band, 30-inch-long Arbalete speargun, and took him to Mission Bay where he told him to spear some stingrays. Again the water was murky, and it was almost like shooting ducks in a barrel.

Then he saw the movie Jaws which put a bit of nervousness into this future record-holding waterman. Little did he know he was slowly transforming from fishing to spearfishing. It just took a bit of time to get comfortable and to adapt.

JOSH ADAPTING YEARS

(click on any photo to view slideshow)

ADAPTING TO THE FREE-DIVING WORLD

Up until he was about 18, Josh would use a rod and reel. He did free-dive, but only occasionally.

So, Josh slowly adapted to the free-driving world where you only go after smaller game, like calico bass and halibut, in the security of the shallow beach waters off La Jolla with no Jaws-like threats. His favorite spots were PB Point, Boomers and WindanSea. Over time, Josh got more confident (gutsy is more like it). He would spend as much as six hours in the water and swim 4 to 6 miles to places like the La Jolla kelp beds, an endurance task that left him dehydrated and beat when he got back to shore. Which was quite dangerous and breaking the first rule of diving — never go out alone, use the buddy system. Even if fishing was his overall desire, it was his fascination with the ocean that captivated him.

Every year several free divers die from shallow-water blackout, including a few that Josh knew, a condition that occurs when someone ascends from a deep dive but doesn’t quite make it to the surface, resulting in a lack of oxygen to the brain. Such deaths are easily preventable by a buddy watching from the surface, ready to help

When Josh was in his mid-20s, he bought a 12-foot inflatable boat and kayak to take him out to the kelp beds and beyond with fishing still being about 70% of his ocean exploits. Diving was still like a side job. Then one day when he was around 30 years old, after his neighbor, Brent Cousino, bugged him for months to fish/dive, Josh finally caved in and grabbed his equipment, gassed up the boat, and they ventured out into La Jolla’s coastal waters.

He wasn’t sure what he was spearfishing for, but when he saw a nice 30-pound white sea bass cruise below him, he took a deep breath and went after the game fish with arms outstretched, grasping the handle of the small speargun, and only by the natural wave of his fins was he able to get closer. When the fish came within several feet from the speargun end, he pulled the trigger and, to his surprise, hit the fast-moving mark. The fish thrashed and fought, the likes of which he had never experienced before.

Then something happened. The dive light switched on! He realized he enjoyed spearfishing more than fishing.

Now what? Then Josh thought about beyond the kelp beds where bigger game lived, like dorado, wahoo and a bigger challenge — tuna. But for the next decade, he focused on inshore fish — bigger yellowtail and white sea bass — which was more satisfying, more of a challenge. They were found in the unusual blue-water environment, where the offshore bigger fish looked at humans as a threat.

MEXICO WHITE SEA BASS HUNT

MASTER THE HUNT IN AN ENVIRONMENT NOT YOUR OWN

How do we accomplish entering a blue-water environment without posing a threat? It’s all about body language and being one with nature. This goes for every species of fish you’ll ever hunt.

Although some fish don’t seem to care about human presence as much as others, blue water fish, and especially tuna, are not on that list. Tuna was a fish Josh knew was the ultimate prize of spearfishing.

More than a few have made spearing a large tuna an item on their bucket list. Some are even surprised when others claim that spearing a tuna is actually pretty easy. Seriously? These are weekend warriors who buy fish at the local fish market and brag to their friends, “Look what I speared/caught today!” And they are the same people who don’t know the difference between a yellowtail and yellowfin.

There are a lot of key factors to hunt this fish, which we’ll get into later, but first is learning how to blend in as much as possible. Sharks, whales and porpoises, none of these larger creatures scare off a tuna – Why? It’s because these creatures are minding their own business and coexisting.

As any good blue-water human knows, one of the abilities you must master in your underwater hunting is the artful skill of stalking (as any military sniper would do). This will help in every aspect of your diving: holding your breath, body language, and the ability to analyze what’s going on around you. Humm. Like sharks?

Then Josh thought, what’s it going to take to go after a tuna that’s 50, 60 or even 100 pounds? Then there was the reality of chats, articles and even YouTube videos of divers spearing big Pacific bluefin northeast of La Jolla near San Clemente.

Josh wanted to be a part of that!

He had already pretty much learned the breath, language and analyzing part, but it sure wasn’t going to happen with the equipment and gear he had.

His opportunity came when he met the men that introduced him to the big-game speargun, where he learned, more importantly, the art of the aspiring spearfisherman leaping forward into the electrifying world of Blue Water Big Game Spearfishing. But like any hunter, Josh had to learn about the game first before he even thought about hunting them.

THE TUNA

Southern California has always been a unique place to dive in the United States. With vast kelp forests, offshore Channel Islands, elusive white sea bass, strong fighting yellowtail and, during the season, small bluefin up to the 60-pound size, it is a place every spearfisherman should dive at some point in their lives.

One time Josh speared a 20-pound yellowtail off the Coronado Islands. A 500lb, 9-foot-long bull sea lion decided that fish was his next meal. The sea lion kept circling within a few feet around Josh, brushing him occasionally while taking salivating jabs at the yellowtail. For a while, this lion played rope-a-dope with Josh. Finally, he had enough of Josh’s perseverance and gave up.

Starting around 2015, the bigger bluefin started to appear after a 80-year sabbatical. When that happened, the fishing and spearfishing mindset was changed and has since been strongly focused on the larger (over 100 pounds) blue-water bluefin, a tuna that had not been readily present for a reason oceanographic experts still disagree on.

Shooting a massive yellow- or bluefin tuna is nothing new in the free-dive/spearfishing world. It has, however, continued to become more attainable for anyone with a serious desire to test their hunting abilities on these incredibly strong fighting fish.

If you have ever hooked a yellow or bluefin tuna on rod and reel, you understand the sheer strength and power of these creatures. Even catching a 30-to-60-pounder on a rod and reel will beat the living hell out of you and can take over an hour to reel in.

Contrary to belief, just because you spear a fish does not mean it is headed for the BBQ. Big tuna have tough skin, larger bone structure and dense muscle tissue. So, to hunt these creatures, one needs a special setup and a speargun that is powerful enough to cut through the resistance of water and with enough impact to tear into the skin, through the body and out the other side so that the slip-tip (a.k.a. dart) gets a good solid grip. Too many times the dart hits its mark but only embeds a few inches in, which allows the fury of a pissed-off fish to rip it out.

Fish are incredibly strong. Any fisherman will tell you that. Unlike big game on land where a missed kill shot only wounds, the game will eventually bleed out and die, and every hunter feels bad because the creature suffers. However, fish can take a powerful wound and still live. Fishermen will tell you it is common to see a chunk of flesh missing and nasty scars on fish from predators, boat propellers and hooks, and in many cases, a spear tip or hook dangling from a fish.

In summer 2020, a fisherman caught a 60-pound tuna off Coronado Island. When the fish was pulled on board, embedded in the fish was the dart, and for God-knows-how- long, the fish had been towing 30 feet of line with a five-foot-long speargun at the end.

Nature has allowed for this iron-clad survival. And all tuna are migratory and skittish. Just because you spot them in one area doesn’t mean they will be there in the next minute, hour or day. Within minutes, tuna can move miles.

On one particular dive about 20 miles off La Jolla at a kelp paddy, Josh speared a nice yellowtail. As he was bringing it in to the safety of the boat, a six-foot mako shark took a nice bite out of it. Which is not uncommon, as any fisherman will tell you, but what is not common is Josh jumped back into the water to see if he could get another one. Needless to say, the captain thought Josh was FREAKING nuts!

If Josh was going to hunt in blue water, he needed the right equipment.

THE LEAP INTO THE BLUE WATER WORLD – THE GEAR

Josh knew that to go after these huge fish, he would need a powerful speargun, heavier float lines, long bungee cords and inflatable floats/buoys.

Josh knew that to go after these huge fish, he would need a powerful speargun, heavier float lines, long bungee cords and inflatable floats/buoys.

When you hit a fish and it takes off, the long bungee cord will give bounce and resistance that helps slow the fish from ripping the spear out and provide drag to tire the fish.

Buoys/floats are an essential part of blue water spearfishing and serve two main purposes: 1) When you spear a big fish, the float will also provide drag, slowing the fish down; and 2) It helps the captain on the boat to keep track of the diver and fish.

Up until Josh was about 20, he used store-bought spearguns or spearguns from his dad’s collection. These spearguns were satisfactory for bass, grouper and halibut, but for anything in the caliber range of 60-plus pounds, it would be like a BB gun trying to take down a buffalo.

One of Josh’s first diving buddies was his good friend, Jamie Chatham. When they were not diving, they were in the garage tinkering with spearguns. Jamie and he had a few. Now add his dad’s armament that they started to dismantle (I’m sure his dad wasn’t a happy camper on this. LOL) and move parts from one gun to another. They had this passion to make their spearfishing better.

Then there was the thought, “Let’s make our own spearguns from scratch.” Not the cheap, cookie-cutter, plastic/aluminum ones you buy in stores.

It first started with the dart, then the trigger mechanism.

Eventually, it moved up to the large wooden guns that were designed after what was then popular for big-game spearfishing back in the ’60’s and early ’70’s, the infamous Attic Gun (old school terminology that even Google or the experts at RIFFE do not recognize), which was nothing more than a 5-to-6-foot wooden gun that had three to four bands. Some had reels attached to reel in the game, and others had a small buoy or float attached to the line. His dad, Keith, helped him build his first wooden speargun.

In addition to his dad, when Josh was about 20, there were two people that also had a significant influence on his spearfishing life — Skip Price (Jamie’s mom’s boyfriend) and Frank Lienhaupel. Both were long-time La Jollans, excellent spearfishermen, and they introduced him to the big-game speargun and encouraged him to make his own spearguns.

But Josh wanted to learn more. So, he picked up a phone book and looked up a couple of members of the famous Bottom Scratchers, Wally Potts and Jack Prodanovich, the team that pioneered modern speargun technology and blue-water hunting techniques. Potts was later credited with the creation of the rubber-band-powered speargun.

The next thing Josh knew, he was in a garage in Point Loma talking to these guys.

The more he mentored from these legends, the more he learned. The more he dived, the more he became submerged into this unique and very skilled water-world sport.

Josh always knew more bands meant more power. American-designed, big-game spearguns are typically made of wood, are bigger and are more powerful and robust compared to their European counterparts. They use thicker shafts which means they can be used to shoot larger game.

Unfortunately, the increased size makes spearguns more cumbersome.

But what if you develop one with additional/thicker bands to improve the overall power and are easy to handle? He also knew that a mid-handle speargun offered more maneuverability and stability.

Josh literally wanted a speargun with a bazooka-like impact that would send his shots flying and with enough power to bury the dart or, better yet, go through the fish. This would better the odds of the dart ripping out regardless of how pissed off the fish was.

So, he and his friends started designing and building spearguns that came with a unique look. He built a small shop with saws, routers, drills, files, grinder and lathes. The handle/triggers were set back a bit further. He made his own shafts, set up his own bands and used teak and/or mahogany for the barrel. On one design, Josh inserted the handle/trigger more into the stock of the gun. This helped make the gun more controllable and with less recoil.

And like a powder-operated gun, instead of rifling the barrel, Josh made sure they were ‘rail guns.’ This means that there is a bit deeper grooved line (rail/track) along the top of the barrel where the spear sits in. This track allows your spear to be guided to give you more accuracy (without this, the spear can wobble slightly) which helped improve accuracy.

So, you have the gear and equipment …and since Southern California is seasonal for these blue water fish … it’s time for road trips during the offseason.

JOSH’S CUSTOM MADE BLUE WATER SPEARGUNS

(click on any photo to view slideshow)

BLUE WATER TRAVEL

Like big-wave surfing or skiing, where surfers and skiers travel to where the big waves and snow are, going after big game will likely require you to travel to where big game is more abundant. Traveling helps with three factors: 1) Traveling to the right place helps you develop how to spot large game like tuna (which we’ll talk about later); 2) It allows you to test your equipment/gear more to ensure a successful hunt; and 3) The obvious: the more practice, the better one becomes.

Then for the next years, he and his diving friends, like Ray Fulks, Keith Wyer and Kevin Scully, traveled south seeking out blue water game fish like dorado, wahoo and, the top-gun of the blue water, yellowfin or bluefin tuna.

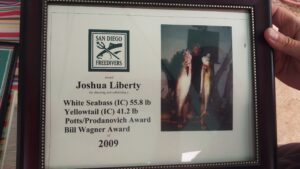

In 2006, San Quintin, Baja California, Mexico, he got about an 80-pound white sea bass, just a few ounces short of the world record at the time.

In 2009, Josh got his first major yellowfin off of Panama. It was about 60 pounds.

In 2015, Josh got an 80-pound wahoo off Mexico.

So, when the tuna found their way up to Southern California, he was out with his friends raking up the kills of big tuna that ranged from 60 to 200 pounds.

In June 2016, Josh nailed his first 200-plus-pound bluefin near San Clemente.

Then about two weeks later, the skills paid off for one of Josh’s dive buddies. Josh and his friends were about 40 miles northeast of La Jolla when they spotted a big breezer.

On this day, June 22, 2016, Kevin Scully scored the California State record for bluefin at 269 pounds and 7 ounces. From that day on, it became this joking tease to take away Kevin’s title.

KEVIN SCULLY’S RECORD BREAKING BLUEFIN

You don’t pick the tuna … the tuna picks you (by mistake) … Josh Liberty

A TASTE OF JOSH AND FRIENDS GALLERY — WORLD-CLASS BIG GAME

(click on any photo to view slideshow)

THE THRILL OF THE HUNT – IT’S ABOUT THE FOAMER or BREEZER

As I mentioned before, tuna are migratory. In Southern California, from as early as April through October or November, bluefin tuna can generally be found in deep schools and swimming on the surface and can range from 50 to more than 300 pounds. However, there are certain indicators that alert you to their presence.

Any hunter will tell you it’s the thrill of the hunt that gets the adrenaline up and running, and there are three ways to find tuna; that is, when you know they are within striking distance.

1) Trolling – For fishermen, it can be the long (boring) hours of trolling, hoping to tease your hook to a creature that you wish is hungry enough to want a taste.

2) Foamers – The adrenaline jumps into warp speed spotting birds diving on bait, and just below are tuna in a feeding frenzy, thrashing violently on the surface — what is known as a foamer. This is fairly easy to spot from a half-mile away with a good set of binoculars. So fishermen will cast the lure or bait into a surface foamer, reel, and this basically masks the lure/bait in the thrashing and is eaten out of aggression.

Many times, boats will run full-throttle towards the foamer and even put divers in the water. Sometimes this amateurism works, but mostly it doesn’t. Rushing straight at a frenzy will scare the fish down deep and/or away from the boat, leaving everyone wondering how their stupidity happened.

When a diver jumps into a foamer (not the most desirable situation), it’s like being thrown into a raging tornado of violent fish, fish scales and white water. It’s hard to see through the turbulence, let alone get a good shot.

3) Breezer – This is when hundreds, if not thousands of tuna are feeding or cruising in a vortex 2-to-30 feet below the surface, and the turbulence creates an updraft surge, which causes a ripple or wake on the ocean surface.

On a calm day, a breezer can look like an isolated patch of wind or, on a breezy day, a patch of calm. Whichever the case, it takes a sharp eye with a lot of skill to spot a breezer because in seconds the ocean can change. One lonely cloud can change ocean colors. Sun glare, sporadic wind causing abnormal ripples, and crisscrossing currents will camouflage a breezer. The ocean can be very deceiving at times as you will learn by clicking on the ‘breezer is not easy to spot’ short video.

With all I’ve mentioned in this article, and on any given day of the hunt, it ALL narrows down to two very important factors — Intel and Teamwork.

JUST ANOTHER HUNT – IT’S ALL ABOUT TEAMWORK AND INTEL – JUNE 22TH, 2019 – A NEW CALIFORNIA STATE RECORD

It was one of those notorious La Jolla June-gloom days. Coastal fog had become a debatable issue for diving, but when the weekend dive and fishing-boat charters started to report large tuna had made their way up to Southern California, Josh and his buddies could not load up the boat fast enough.

There are two vital keys to catching big tuna:

1) INTEL. As I have said before, tuna are migratory. So, knowing they have been spotted doesn’t mean they will be at the same location when you arrive.

Fishermen/divers will pick up radio chat of where tuna is spotted, which is important to a diver trying to track them. Chartered dive and sportfishing boats normally go after the smaller tuna that range in the 60-pound schools where bigger schools are not far away. For this particular trip, Russ Slaughter’s boat and diver went with Josh and his two divers. From the second they left the dock, they were in constant radio communication with each other while monitoring the chat of other boats on various radio frequencies and marking these locations on a GPS. Then they calculated where they will allow for currents, tides and mild variation of ocean temperature.

2) TEAMWORK. In Josh’s boat (The Pez Loco), there was Keith Wyer and Kevin Scully and all were keeping a sharp eye out for birds working foamers or breezers along with Russ Slaughter and his diver. More eyes the better. Beforehand, Josh and Russ had established a strategic plan, which was working in the same general area that they thought the fish would be from compiling intel from the charters and other boats.

Their strategy worked. About midmorning, The Pez Loco found a breezer of large bluefin, and the best part, not a boat was in sight. As ironic as it was, both boats had zeroed in on the same school. They approached in stealth and flanked the school with teamwork precision.

All of Josh’s diver buddies are skilled captains, and they take turns being captains after they score. Since Keith Wyer’s got the last score, it was his turn, and now he has two critical jobs. The first one is the most important — watching out for the safety of the diver(s); and the second is maneuvering the boat in close, but not close enough to spook the fish. And if there is a wishful third, once the diver has landed the catch, help him bring the catch onboard.

Russ’s diver hit the water first and nailed the first tuna within a few seconds, and then a few seconds later, Kevin from Josh’s boat, scored a hit. Unfortunately, both tuna ripped out the dart. The day was not starting off well…but it was about to change.

Josh was also in the water with a vortex of fast-moving tuna crisscrossing around him. He had seen several, but they always seemed to swim out of range. Josh held his breath and continued to glide down 30 to 40 feet to prevent any disturbance in this deadly technique. Gliding eliminates the vibrations from fin kick and is much stealthier. He waited silently until one tuna he guessed was about 180 pounds came within range of the gun.

One of the keys: Do not jerk the gun. Keep it in an outright, fixed position until the fish swims in front of it. And when this tuna swam in front, making the mistake of pausing for a split second, that’s when Josh pulled the trigger.

The shaft hit its mark, and instantly the fish took off like greased lighting toward the surface.

Meanwhile, on the surface Keith Wyer spotted the buoy suddenly take off. Then, to his surprise, the bluefin leaped out from the surface in a column of white water and started to freak out by flip-flopping across the surface.

When Russ from the other boat yelled, “Holy f***, is that a speared fish?” Keith knew Josh got a big one.

But right now Keith’s only concern — in what seems like forever seconds — was hoping Josh’s head broke the surface for air — soon. When that happened, his next concern was seeing 100 feet of Josh’s bungee cord and 30 feet of shooting line thrashing around.

Also, keep in mind that Keith now must juggle his watchful eye for the safety of the other diver, Kevin. His eyes kept flip-flopping to Kevin and Josh.

By now Keith’s head was filled with the question, “What can happen when things go wrong?”

The first thing a diver does is line management, staying clear of bungee line and spear line so he/she doesn’t get tangled up and get hit by the buoy as it races by you pulled by an angry tuna — or get hit by the fish in its fury. A 200-pound-plus fish hitting a human is like being hit by a concrete missile –- death could be instant. A tuna will also circle, which can literally lasso a diver in line and bungee cord, pulling the diver down to drown them. He also expected Josh to swim like hell chasing the buoy, another exhausting feat.

But Josh had made a good shot. His dart hit the spine, which partially stoned it, BUT did not kill it!

After the fish came crashing down on the surface, and Josh was treading water, the bluefin circled around. It was now line management, making sure he was keeping clear of the bungee cord and spear line. Unknown at the time, the fish had died, allowing Josh to pull it to the surface within ten minutes.

Normally, this can be an extreme workout if the fish is still alive and can last over an hour, as Kevin’s record did. Think about treading water with a full wetsuit on, 20 pounds of weights and speargun while pulling up 200-plus pounds of deadweight or worse and a fish instinctively still trying to get away. Or constantly diving down and swimming to the surface pulling a fish up. One must be in excellent physical shape.

And yet knowledge, experience and intuition tells you things could still go wrong. Again, the fish could get a second wind, dart and begin circling, wrapping the bungee cord around Josh and dragging him down, or the predators of the sea – sharks — would come racing, sensing the blood trail. So teamwork jumped into action.

But with teamwork and good luck, the above never happened. Keith got the boat alongside, and when Josh got the fish bucking its head against the hull of the boat without movement, he had officially landed it. With that said, Keith, Kevin and Josh were able to manhandle the fish on board with a lot of grunts and heave-hos.

Once Josh caught his breath, and after a few photos were taken, Kevin took a hard look at it. He made the comment, “Josh, the fish looks bigger than mine” (alluding to his record). One of the things they did was measure the girth and length of the fish to get an estimate of weight. Then do a bit of math. Yes, it was more weight.

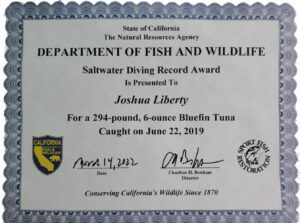

It took a bit of coaxing before Josh said, “Okay. Let’s get it weighed on an IGFA (International Game Fish Association) certified scale at Dana Landing.”

And, as redemption would have it, the two that lost their fish were able to score, with Kevin getting a 260-pounder later in the day, and the diver on Russ Slaughter’s boat got one over 260 pounds. It now was a great day, and it was about to get better for Josh … but it took almost THREE YEARS!

At the landing, the fish weighed more than Kevin’s record of 269 pounds, 7 ounces. Josh submitted the red tape application in July 2019. He then waited almost a year with not a word heard back (they only give you a year to refile). He once again resubmitted in June 2020. Again he didn’t hear back. He thought it got lost in the bureaucratic shuffle because of COVID-19. Then in March 2022, a letter came from the Department of Fish and Wildlife that Josh now held the California State Saltwater Diving Record of a 294-pound, 6-ounce bluefin tuna (along with a nice certificate). He had beaten Kevin’s record by 25 pounds and 1 ounce exactly six years later, same month and date.

Josh was almost 50 years old when he scored the state record, and Kelly Slater was just a week away from turning 50 when he won the Billabong Pro Pipeline 2022 surf competition. Which goes to show you … being older means there is no better skillset than years of experience and commitment.

So, what’s been up for Josh, Kevin and Keith for the last three years, with the lucky month of June here? I think we all know the answer to that.

Albert’s Note: When spearfishing out of the country, Josh and his friends will only bring back what U.S. Customs allows, and the remaining meat will be given to locals or local charities. When diving in the U.S., when it comes to certain species like bluefin, even though a diver is allowed two bluefin a day, in conservation, one is usually all one diver will take. They have no problem giving it away to family and friends.

[su_divider top=”no” size=”2″ margin=”20″]

Albert thanks all the photographers, Bill Decker and Melinda Marquardt, who made sure Albert kept in line while writing, which, as many know, is almost impossible to do.

“the infamous Attic Gun (old school terminology that even Google or the experts at RIFFE do not recognize), which was nothing more than a 5-to-6-foot wooden gun that had three to four bands.” I recognize this as a gun designed by the Addict Diving Club. Formed after the Bottom Scratchers, they took home many diving competition awards! Frank Leinhaupel takes credit for this design.

When you say “Attic Gun” do you mean the spear gun that was designed by members of the Addict Diving Club (including Frank Leinhaupel)? Josh can verify this!

Great story. From physical therapy to sport fishing; glad you found your calling, Josh. You have a world-class teacher. Love you both.

Sabrina

That was an amazing read Kip, good job! I wish I had his courage when I was young, after JAWS I was spooked to go spearfishing! His dad taught me how to do shore-fishing and harpooning blue sharks. Great memories from the late 60’s.

Josh has a lot of courage to go free-diving for those big tunas!

Ray Townsend

I knew who Keith Liberty was from when he worked at Ocean Fresh and hadn’t heard the name in decades until now. he’s an legend in La Jolla and great fishermen but never knew about his son. Wonderful father to son story. Keith, I’m sure is very proud of his son. Thanks Kip for another great read about La Jolla.

Nice pics and photos.. I went to school with your dad and uncle Kenny.. Fished on Scripps pier in the fifties and quite often would bump into your dad. He showed me how to use a half or whole mackeral to catch the abundant leopard sharks just outside the surf line. As we got older and both had our own boats we often would run into each other of Pt La jolla fishing. Great fishing and spearfishing those days in the 50,60, 70’s. Not so much locally anymore. Wayne Kanakaris

Breeser, also called bait ball. Drop. A bone jig in and fast troll through it. Every time wham. Big fish.

That video of the breeser is great – never would I have know. Thanks for the excellent read and will share …

Holy Shit! what a great article and waterman …. man would I love to have a few of those bluefin steaks. The best. Thank you Mac Meda for sharing this …